Ballettexpertin und Ballettmeisterin Patsy Kuppe-Matt 2021 in Stuttgart, vor der Kulisse des Opernhauses. So eine tapfere, kenntnisreiche und dennoch liebevolle Person! Sie wird stark vermisst… Foto: privat

Sie war ein feiner Kerl. Fair, aufgeschlossen, präzise, humorvoll. Und sie war hübsch, denn auch im vorgerückten Alter sprühte sie nur so vor Charme und authentischer Liebe zu fast allem, was sie umgab. Ihre Art Schönheit kam von innen, und das war auch ihr Credo, wenn sie Ballett unterrichtete oder Trainings unter anderem beim Stuttgarter Ballett leitete. Ob als Tänzerin in jungen Jahren oder als Gastballettmeisterin in den späteren: Sie machte Mut, Ballett als Kunstform zu verstehen – und nicht als eine Art Sport in Kostümen. Und wer sie kannte, empfindet es als höchst ungerecht, dass Patsy Kuppe-Matt, auch unter ihrem Mädchennamen Patsy Kuppe-Loew bekannt, gestern im Alter von nur 63 Jahren auf Ibiza, ihrem Wohnsitz in den letzten Jahren, verstarb. Sie hinterlässt außer vielen herzlich verbundenen Freund:innen einen erwachsenen Sohn namens Raphael, dessen Vater Christopher Matt ebenfalls als Trainer arbeitet, sowie ihren Ehemann David. Weltweit aber trauert die Ballettgemeinde um eine heimliche Koryphäe, die weniger nach großem Glanz gierte, als dass sie an stimmigem Austausch und intensiver Wirkung interessiert war. Und sind solche Personen nicht die wahren Sterne?!

Patsy stammte aus Stuttgart, wo ihre Mutter eine angesehene private Ballettschule führte. Traudl Kuppe-Loew war denn auch die erste Tanzlehrerin ihrer Tochter. Und deren Funken sprühendes Talent war offensichtlich – es führte Patsy nach Cannes zu Rosella Hightower und weiter bis nach Monte Carlo.

Auch später als Tänzerin in Paris und New York lernte sie weiter, unermüdlich und stets neugierig wie am ersten Tag: auf neue klassische Ansichten, die sie erlernte, ebenso wie auf moderne Tanztechniken – bis hin zur Bewegungslehre von Alexander Feldenkrais.

Patricia Neary aus New York City, hier als Abgesandte vom Balanchine Trust beim Ballett der Mailänder Scala zu sehen, lehrte Patsy Kuppe-Matt. Foto vom Schlussapplaus in Mailand: Franka Maria Selz

Patricia Neary, die Balanchine-Muse, war wohl die berühmteste ihrer Lehrerinnen. Patsys Liebe zur Genauigkeit, aber auch zur Fröhlichkeit im Tanz mag dabei kultiviert worden sein.

Im Herzen war sie multinational und multikulturell, sprach neben Deutsch und Spanisch auch Englisch und Französisch.

Aus der vielseitig interessierten Patsy, man ahnt es, wurde nun keine Primaballerina, aber eine hoch geschätzte Kollegin im internationalen Tänzervolk. Sie trat beim Bayerischen Staatsballett mit Konstanze Vernon auf, tanzte zudem in den Ballettmetropolen Paris und New York sowie in Denver und Trier – glückliches Trier – und natürlich beim Stuttgarter Ballett.

Dieser Company blieb sie denn auch stark zugeneigt, obwohl sie in Spanien ihre eigene Karriere auf die Spitze trieb: Für fünf Jahre war sie ab 1999 Ballettdirektorin in Saragossa. Als solche kreierte sie selbst einige gefühlvolle Stücke und ließ Werke von William Forsythe, Nacho Duato, Nils Christe, Uwe Scholz und Davide Bombana einstudieren, wobei sie selbst bei den Proben assistierte – und das kleine Ballett von Saragossa bekannt machte.

Angel Corella holte Patsy Kuppe-Matt zu seiner Company in die USA. Foto: PR

Danach genoss sie ein Leben mit stets viel Reisegepäck im Anschlag: außer dem Stuttgarter Ballett holten das Wiener Staatsballett, das Théatre du Capitole in Toulouse, Angel Corella in den USA sowie die Forsythe Company in Frankfurt, Gauthier Dance in Stuttgart und etliche weitere große und kleinere Truppen Patsy Kuppe-Matt als Gasttrainerin.

Eigenwillig und meinungsstark, aber aufgeschlossen genug, um zu diskutieren und zu lernen, verströmte Patsy Kuppe-Matt jenes Flair von Kunstaffinität, das es wert ist, die Branche Ballett am Leben zu erhalten.

Kalte Technik und schnöder Kitsch waren ihr ebenso zuwider wie virtuose Angeberei ohne Sinn oder auch völlig überfrachtete Symbolismen.

Patsy Kuppe-Matt auf Reisen, hier 2013, ganz in ihrem Element, um den Geist des Balletts durch die Welt zu tragen. Foto: privat

Ich habe es sehr schade gefunden, dass Patsy nicht auch Kritikerin war und auch nicht sein wollte – das Zeug dazu hatte sie allemal!

Das weiß ich so genau, weil ich einen durchaus regen Kontakt zu ihr hatte.

Gelegentlich chatteten Patsy und ich, und dann ging es meistens um die Kunst.

Zuletzt war das am ersten Januar 22 der Fall, als sie sich bei mir über das in diesem Jahr teilweise wirklich misslungene Neujahrskonzert mit den Wiener Philharmonikern beschwerte. Die Pferdeshow in der Fernsehsendung sei noch das beste gewesen, witzelte sie – aber vom Wiener Staatsballett und den choreografischen Einfällen von Martin Schläpfer war sie enttäuscht.

Obwohl wir an manch anderer Stelle hart diskutierten, pflichtete ich ihr hier vollauf bei. Und ich empfahl ihr anzusehen, was mich zur Jahreswende selbst beglückt hatte: das letztjährige Silvesterkonzert der Berliner Philharmoniker, das im Internet weiterhin zu bestaunen war.

Sie konnte es ebenso genießen wie ich. Dirigent Lahav Shani entlockte da dem 1. Violinkonzert op. 26 von Max Bruch mit Janine Jansen an der Violine ganz neue Facetten, mit einer Tiefenschärfe, als blicke man auf den Grund eines klaren Bergsees.

Vor nicht ganz zwei Jahren erst hat Patsy ihre Mutter beerdigt, die ebenfalls auf Ibiza lebte und in Stuttgart bestattet wurde. Wir denken an sie und vermissen sie – und unser Schmerz über ihren Verlust soll niemals enden, wiewohl und weil sie uns immer so sehr viel Kraft gab und gibt.

Gisela Sonnenburg

„And dance for me, darling!“

For all English readers and for all who loved Patsy, I made an interview with her very close friend, the former dancer Karen Montanaro:

Ballett-Journal: Since when did Patsy Kuppe-Matt know about her disease? And was there hope first? Why, do you think, didn’t she out herself? Because of her strong character?

Karen Montanaro: I don’t remember the exact date when Patsy learned she had breast cancer, but it was several years ago. She had surgery and underwent chemo and radiation. She lost all her hair. She didn’t tell many people about it. Patsy didn’t want people to worry about her or feel sorry for her. She didn’t even tell her mother, Trudy! (Traudl Kuppe-Loew who owned the Ballettschule Kuppe-Loew in Stuttgart.)

Patsy definitely had a strong character and did not “buy into” the whole medical approach to her problem. She was deeply conflicted about chemo and radiation and suffered many of the typical side effects. She really wanted to stop all the treatments and at the same time, she was afraid of stopping them.

For at least a year, she was under the impression that these treatments would cure her. It was a bad day when her doctors told her that there was no cure and that the most she could hope for was a treatment that would prolong her life and stave off this inevitable death sentence.

Patsy talked openly with me about her treatments, her pain and suffering, her fears, her hopes, her anger and frustrations. I think she trusted me to stay strong for her and we had many wonderful, deep conversations about miracles — where they come from and what they mean. She was not religious, but she certainly believed in miracles. I believe this is why she loved ballet so much.

As you said, she had an “inner eye”. She could see deep into the soul of her dancers and many of them credit her with nurturing that soul and making it visible through the love she had for this unique beauty within.

Karen Montanaro and Patsy Kuppe-Matt: friendship for so many years now… Thank you to both of them! Photo: private

Ballett-Journal: She was a very precise teacher and balletmaster, and her „inner eye“ was very strong. Can you tell me something about her in this regard, maybe an anecdote?

Karen Montanaro: This is one of my favorite subjects! Patsy’s inner eye! She taught some of the very best, most technically proficient dancers in the world and many of them were uptight, insecure and intimidating, but her love of “deep dance” helped her see through these defenses. Patsy’s inner eye helped her see things. She trusted it and spoke from it. One time, she told a particularly unhappy-looking dancer that her arabesque was beautiful, “The only thing lacking is the carrot on top of the cake.” She was referring to the carrot-shaped frosting on top of a carrot cake. The dancer was delighted with the image. She loosened up and started dancing with more freedom and joy. This “carrot” became a kind of shorthand for Patsy and me, whenever we referred to the je ne sais quoi that Patsy could see so easily in her dancers — even when it was not visible.

Ballett-Journal: What was her way in her youth like from Stuttgart to the world?

Karen Montanaro: Patsy moved away from Stuttgart in the early 80s in order to dance in the Moulin Rouge. I often visited her there. I was dancing with the Darmstadt Ballet at the time and whenever I had a break, I hopped on a train to visit Patsy. We would take class with Peter Goss (an amazing, inspired modern dancer in Paris) in the afternoon and then I’d hang out in Patsy’s four-story-walk-up studio apartment until after her shows at the Moulin Rouge. Then we’d stay up drinking wine and talking about everything under the sun until the wee hours in the morning. Our conversations were always deep — philosophical, idea-based, conversations about “God and the world.” Patsy was never petty or superficial. All of her life-experiences had a magical luster and significance for me and I could listen to her talk for hours!

She met and fell in love with Christopher Matt in Paris. He was a ballet dancer with a similarly deep love for the art form. The couple moved to Stuttgart where they had a son Raphael. Soon after that, however, the three of them moved to Yugoslavia. Patsy became the ballet mistress of the ballet company there and Christopher danced in the company. The couple eventually separated but have remained close friends. Patsy met David, her current husband, in Spain. She originally hired David to babysit for Raphael while she assumed her position as ballet mistress for the Zaragoza Ballet. Since then, Patsy was totally immersed in the ballet world and gained a world-wide reputation as being one of the best teachers around.

Karen Montanaro flying in a beautiful photo made by Michael Menes.

Ballett-Journal: May I ask you how you came to know her, please? And please tell me your most important memory with her.

Karen Montanaro: I have so many but I’ll tell you how we met. Both of us were in our early 20s. I was a professional ballet dancer but I was unemployed and extremely miserable. In America we have an expression for ballet dancers like me. We call them “bun heads.” (Ballett-Journal: I would love to expurgate this term, it is not what they deserve!) And I was one of the tightest, most self-loathing “bun heads” in the world — or so it felt. As an unemployed, fanatical ballet dancer, I often contemplated suicide. (Not that I’d ever actually commit suicide, but I certainly thought about it a lot.) I had just quit my last ballet job with the Ohio Ballet because I was injured all the time and I couldn’t stand to be undependable. The most serious injury of my career was a fracture of the spine for which I had to wear a back brace for a year — right when my trajectory in the ballet world seemed most promising. At my lowest ebb, I decided to follow my sister, Susie, to Germany. She planned to marry a German man and I decided to audition for ballet companies over there. In addition to auditioning, I made one unbreakable rule for myself: I had to take a ballet class everyday. Susie lived in Tübingen and the nearest city where I might find a competitive ballet class was in Stuttgart. I had a magazine of dance resources and was particularly attracted to the photo/advertisement for the Ballettschule Kuppe-Loew. It was not a typical ballet photo — just a pair of legs from the knee downward in a regular standing position — but you could tell that the legs belonged to an accomplished ballet dancer. I learned later that Patsy had taken the photo.

The address of the school was: Traudl Kuppe-Loew Ballettschule im Marquardtbau am Schlossplatz, 70173 Stuttgart.

Historical Marquardtbau in Stuttgart around 1900. Photo: anonymous

So there I was in the Marquardtbau ready to take an afternoon class. I was all dressed in my favorite purple leotard and black skirt, tights and pointe shoes (I always took class on pointe) warming up in the hall but I needed to go to the bathroom. I wandered out into the hallway looking for a bathroom. Just then, a tall, willowy, thin, gorgeous woman emerged from the elevator. I asked this woman, “Wissen Sie bitte — wo is die toilette?” My German was terrible. But Patsy looked at me as if she already loved me. In English she told me that I was walking in the wrong direction and that I must be cold out there in the hallway. She showed me where the bathroom was. During class, I often saw her watching me. After the class, she invited me to take the morning adult classes with Hitomi (a former Bejart dancer) and to take as many afternoon classes as I liked free of charge. I was gobsmacked and grateful!

I met Patsy’s mother, Trudy, the next day and Trudy (an Anglophile with a lovely English accent) told me that Patsy had already told her about me. According to Trudy, Patsy told her mother that I would go mad if I could not dance. I wondered how Patsy could have seen that in me. I hadn’t acknowledged this truth to myself, but as soon as Trudy said it, I knew that Patsy had “seen me.”

In the next few weeks of our friendship, Patsy did for me what she continued to do for “bun heads” all over the world. She lightened me up (!) and helped me enjoy life again. During our first social time together, she took a large pair of scissors and cut off my hair. at which point my hair “pouffed out” in a pixie cut. Patsy held up a mirror and I instantly started crying because I loved my “new look” so much! Then she took my long, heavy, dark winter coat and told me never to wear it again. Instead, she gave me a bulky, brown and white checkered sweater from Yugoslavia and a pair of brown and white stripped pants that she no longer wore. I was permanently changed after that. That was almost 40 years ago and Patsy and I became closer and closer over the years. I miss her tremendously, but I also know that she lives and dances in me.

Her last messages to me was:

„I am lost

But I’ll try to sleep now

Dance for me darling”

Ballett-Journal: Thank you very much, dear Karen. Let’s take a cup of kindness thinking of Patsys power forever.

Interview: Gisela Sonnenburg

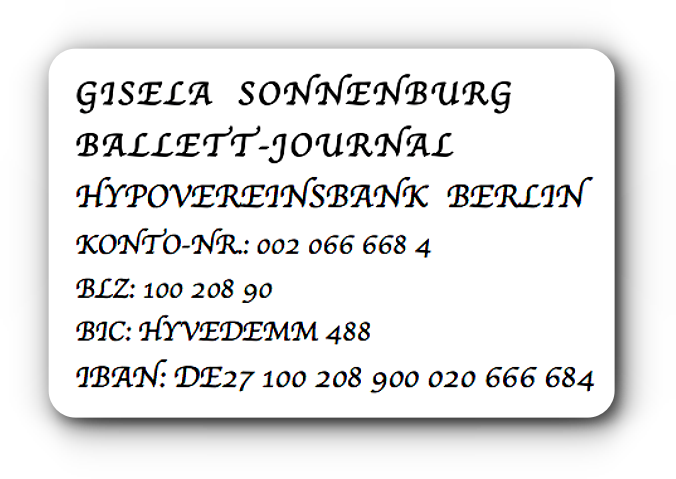

Lesen Sie hier, was nicht in BILD und SPIEGEL steht! Und spenden Sie! Journalismus ist harte Arbeit, und das Ballett-Journal ist ein kleines, tapferes Projekt ohne regelmäßige Einnahmen! Wir danken es Ihnen von Herzen, wenn Sie spenden, und versprechen, weiterhin tüchtig zu sein!